Sailing Back Across the Atlantic

Time to Leave the Mediterranean

After sailing across the Atlantic to the Mediterranean in 2015 and spending two seasons there, it was time to head back so we could fulfill the dream of sailing the South Pacific before grandchildren come along. During our time in the Med our travels took us to Portugal, Gibraltar, Morocco, Spain, France, Italy, Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia, Herzegovenia, Slovenia, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Austria, Germany, Czech Republic, Hungary, Greece and Turkey.

team hug

We sailed all the way to Turkey in the fall of 2015 and began our slow westerly journey from there in March 2016. Turkey was one of our favorite countries for its scenic diversity and beauty; the kindness and hospitable nature of its people; its rich culture and history; remote, unspoilt villages and coves; beautiful ports and marinas; and ideal sailing conditions with the cleanest water and shoreline in the entire Mediterranean. Turkey is also outside Schengen, so staying there stopped the ticking clock that gave us only 90 days in a six month period in Schengen signatory countries. Reluctantly we left Turkey in late June 2016 after the political situation became untenable and terrorist bombs tore apart the exact part of the Istanbul airport we had walked through four days before.

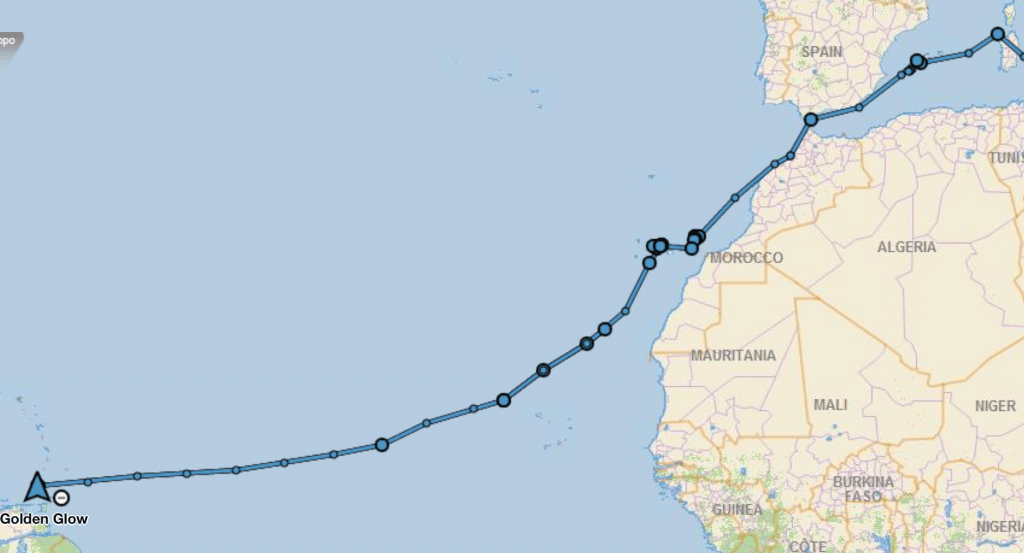

Our Route Across the Atlantic

After sailing as far south as the Libyan sea on the south side of Crete, north up the Adriatic, and even doing a eurail “Mad Dash” trip inland in eastern Europe in August, we arrived back in Gibraltar on September 30th to prepare for the crossing.

sunsets like this were an every evening occurrence mid-Atlantic

Our plan was to take our time enjoying the Mediterranean as we sailed back from Turkey to Gibraltar by the end of September. From there, after readying for a month crossing the ocean, we would spend some time in Morocco (which we’ll describe in a separate post), then go to the Canary Islands (also a post to itself), and then as the saying goes, head south until the butter melts, before turning west. We would stop in the Cabo Verde Islands off the coast of West Africa if time permitted or weather demanded. In the end, by the time we made landfall in Grenada, we had sailed about 4,000 miles or so since leaving Gibraltar, which brought our total miles sailed to 23,000 or so.

Gibraltar

We pulled into the fuel dock in Gibraltar at around four in the afternoon. The 30th was a Friday and I wanted to try to make it to customs before they closed to pick up some Harken blocks and other items I’d ordered from the States. If I could get them before the weekend, we’d have the option to leave sooner and have more time in Morocco before we had to get to the Canary Islands to pick up Hunter and Reid.

approaching Gibraltar from the east

Customs was just a few blocks from the fuel dock so while the boat was being fueled I jumped off and ran, getting there by 4:30. Alas, I discovered they closed early on Fridays at 4 – and wouldn’t be open until the next week.

Gibraltar is an excellent place to provision. There are many excellent suppliers and they use the British pound, which has dropped to a favorable exchange rate against the dollar. On top of that, Gibraltar offers the best prices in the Mediterranean on liquor and fuel. Diesel prices were less than one-half what they were in Mallorca.

Gibraltar also sits on a peninsula jutting out from Spain and the border town was just across the airport from Ocean Village marina where we were berthed. I biked or walked across the border to Linea de la Conception, Spain almost daily because there were many good suppliers and services there including the best Volvo parts dealer in the area.

our route from Gibraltar to Rabat Morocco

Monday came and we picked up our items at customs, completed our provisioning and were ready to depart. Leaving Gibraltar, we needed to make a stop to pick up some sails a few hours west of Gibraltar in Spain before we crossed to Africa, so we timed our departure carefully to give us the benefit of best currents, tides and winds.

Navigating the Straits of Gibraltar requires planning and good execution. The tides and current are very strong, and the winds can also be powerful because of the narrowness of the channel and the shape of the land masses on either side.

The challenge is that Gibraltar’s currents and tides are very powerful and constantly in flux. Our stop in Spain had to be as fast as possible to keep us in the narrow window before tides and currents became our foe instead of our friend.

Our sailmaker had assured us that he would be waiting on the dock for us so we could hand him the money for the repair and he would hand us our sails. He also said he had spoken to the coast guard in his town and it wouldn’t be a problem for us to sail into the harbor to do the quick exchange without checking-in to Spain first.

The winds were ferocious as we approached the not-very-protected harbor. We pulled in and the first boat we saw was a coast guard vessel filled with keenly attentive sailors. The sailmaker beckoned us to the quay, but as we tied up it became apparent that the coast guard wanted an explanation of why we were there and what we were doing. Our sailmaker and the coast guard captain engaged in a rapid Spanish dialogue and it became clear that they weren’t thrilled with what the sailmaker had arranged, but they’d let us get our sails if were were super-quick. That suited us fine, and we were out of the harbor in record time.

Once we left Tarifa, we still had a difficult task ahead of crossing all the shipping lanes and getting around the point at Tangiers before the tide turned. Rand charted our course brilliantly and navigated us through a mass of enormous freighters and cargo ships without anyone having to change speed or alter course.

The African Coast

As we got out into the Atlantic and started down the coast of Morocco, the sea temperature dropped about 20 degrees and heavy coastal fog socked in. There were many, many fishing nets and unlit fishing boats in our path, so the trip down the coast was not an easy one. Moroccan fishermen use driftnets hoping for swordfish, even though they have been condemned by the international community. The driftnets result in the inadvertent netting and death of turtles, crustaceans, bird and other sea creatures. The nets also could ensnare our propeller, and we were using our engine in the windless fog. We had a few close calls where we saw the nets in time to cut the engines or alter course, but it was a nerve-wracking night.

Moroccan fisherman with their nets

We made our Moroccan stop in Rabat, which was recommended as the best port on Morocco’s Atlantic seaboard. What a challenging entrance it had! More about that in a separate post.

Our sail from Morocco to the Canaries was perilous at first because the nights were moonless and very dark and the coastal fishing situation was like a minefield of nets and boats and buoys to avoid. Once we were clear of the fishing zone, we had a good sail to Lanzarote, the first of several Canary Islands we would visit (another post).

From the Canary Islands to Grenada

We had generally very favorable conditions sailing from the Canaries to Grenada. There had been a major storm that hit the Canary Islands right before we began our transatlantic passage. In fact, the waves were so large that we postponed sailing for a day. When we did leave, we had very strong winds for the first 24-48 hours, then they got quite light, as is to be expected in this region in the fall.

We stayed as close as we dared to West Africa and watched weather conditions carefully. I spent hours each day downloading weather files using our new Iridium Go that I’d had shipped to Tenerife to meet us.

We continued to run models daily to help us chart the “optimal” course. Some models that gave us data for the fastest passage would have had us sail due west, which we decided against given that all the worst storms we’d seen veered up into what would have been that path.

Weather

sunset behind southern latitude storm clouds

It’s interesting that Columbus sailed most of his voyages leaving in the summer – hurricane season! For example, on his most famous voyage, he set sail on August 3, 1492 and reached the Bahamas on October 12th. Not having the King and Queen of Spain to back us, we have to mind our insurance carrier who wouldn’t cover us if we were west of longitude 30.5 before November 1st. Interestingly NOAA has now extended its hurricane season through November 30th because even though the main hurricane season is from June to October, hurricanes have been known occasionally in November and very rarely in December.

we flew our code zero and parasail wing-on-wing for many miles

Hurricanes frequently start well out in the Atlantic Ocean, often on the latitude of the Windward Islands that we sailed for much of the passage, known as the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone. The ITCZ is a belt of low pressure which circles the earth near the equator where the trade winds of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres come together. It is characterized by convective activity which can generate powerful thunderstorms over large areas. Even if we didn’t encounter a full-blown hurricane (when the winds exceed 64 knots), we wanted to avoid “Tropical disturbance,” “tropical wave,” “tropical depression” and “upper level trough” “tropical storm” and convective squall activity too as they can be very nasty, so we turned on and checked our radar every 20 minutes through the nights to see them coming, try to avoid them, and reef in sails and be prepared if they were going to overtake us.

some sail repair en route

Trade Winds.

The other advantage of sailing later in the year than Columbus, besides avoiding hurricanes, is that the stronger trade winds blowing from east to west that we wanted to power our voyage don’t pick up until wintertime. In the Caribbean, they are called “Christmas Winds” because around Christmas is when they really start to blow, often with sustained wind speeds in the 25-30 knot range. Frequently during the period from early December through mid January or so, the easterly trade winds become stronger and remain moderately strong for a period of least several days, sometimes more than a week or so.

Reid up the mast

clipped in and out of the bowsprit at night

Hunter up the mast

For us, sailing in early November (to be able to reach the other side and fly to the USA in late November for Thanksgiving with our family) meant we were a bit early for the well-established trade winds. We lucked out and did enjoy pretty decent winds, which we maximized by sailing with two huge headsails, wing on wing. And we probably had much steadier winds than Columbus, which may beone reason why our passage was so much faster than his.

If you’re curious, here is why Christmas Winds develop. The Atlantic subtropical high (also known as the Bermuda High) plays the major role. This high is present in the Atlantic almost all year, but its position shifts with the seasons, and its size and strength also varies. Typically, the high is larger and stronger during the summer months. It is also usually centered at higher latitudes (in other words, farther north) in the summer. We experienced a HUGE high pressure system when we sailed east from Bermuda to the Azores across the northern North Atlantic in May 2015.

During the transition from the warm season to the cold season, the “storm track” of lows progressing from North America generally eastward over the North Atlantic shifts farther south, and there is a corresponding shift southward of the subtropical high. Even though the high usually becomes smaller and weaker during this time of year because it shifts farther south (usually to somewhere in the 25 to 30 degree north region) it induces a stronger pressure gradient between its higher pressure and the lower pressure farther south toward the equator. This increased pressure gradient leads to stronger winds – the “Christmas Winds.”

Mid-Atlantic Excitement, Calm and Daily Work

We stopped mid-Atlantic to swim in the warm water, here Reid, Rand and Hunter frolic while I woman the boat

ukelele zen on the foredeck

A passage of almost a month is going to bring moments of zen and excitement, and this one lacked for neither.

double-rainbow zen

A view of Golden Glow as I swam behind the boat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

Hunter got the cleanest fender prize

We also each did something to service the boat every day. There was still plenty of time for music and laughter, lots of card games, cooking and sharing good meals, swimming off the boat, watching dolphins, flying fish and weather systems, watching sunrises and sunsets.

With ITCZ wind dynamics, we did have a few “all hands on deck” to hurriedly bring in sails and sometimes deal with challenging situations. The boys both got to go up the mast in good weather for practice to experience that. Overall, the passage provided them great learning experiences and an adventure and sense of accomplishment we hope they will remember and will serve them well throughout their lives.

Sargasso Sea

Just as Columbus noted he was nearing land when he began sighting what he called “sargosso weed,” and more seabirds, we started seeing more and more of the seaweed as we reached the Sargasso Sea east of the Caribbean.

We wrote about our first encounters with Sargasso seaweed two years ago. We were fascinated by its uniqueness because it is free-floating or “holopelagic,” meaning it reproduces vegetatively on the high seas, and never attaches to the floor of the ocean during its lifecycle. But we also remembered what a pain it was when we were fishing, constantly getting caught on our line.

Atlantic Catch – and Release

Within a few hundred miles of Grenada, despite the Sargasso seaweed, we caught an enormous, very beautiful Dorado. We were using a small hook, hoping for a small catch, and we were astounded to have brought in such a huge fish. Its heft saved its life. It was too large for Rand and me to eat it in the few days left on the passage (the boys had become vegetarian shortly before the passage) we never wanted to catch more than we could eat. So we bade the Dorado farewell, unhooked it and returned it to the sea.

![]()

Hi there,

I just heard back from Memo, October 2018 is the first available slot. That’s a very long wait, as an alternative I’m thinking about having a look at a Dashew FPB64 available immediately. We’ll see, just wanted to let you know I managed to get in touch with them thanks to your help.

Be safe,

Erik.

Thank you very much for your help, I will get in touch with them today.

Happy sailing,

Erik

Hello,

I’ve been trying to get in touch with the Antares factory in Argentina but I’ve not had any luck so far. I cannot find an adress/phone number on their site and the contact form gives an internal service error. Are they still in business? Could you please tell me how to get in touch with them, I would like to visit the factory and place an order. Thank you for your help, happy sailing!

Regards,

Erik.

Hi Erik, you can reach the Antares factory with this contact info. Talk to Memo about placing your order. There’s a pretty long waiting list I believe because they only build a certain number of boats every year and they have orders in the queue, but sometimes people postpone and the order moves around. Good luck. The Antares 44i is really a superb sailing vessel!

Mob. + 54 9 11 15 6361-6327

Tel/Fax + 54 11 4725-2143

+ 54 11 4745-1074

memocastro@40gradossur.com