Save the Oceans, Feed the World

Bloomberg’s New Plan: Save the Ocean, Feed the World

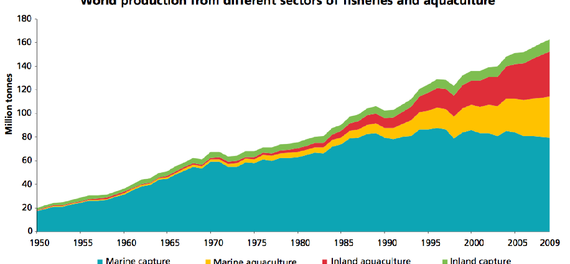

The global demand for seafood and fish products is expected to rise by 20 percent between now and 2020. Many countries are now supplanting their dwindling harvests of wild fish with farmed fish. The aquaculture boom has its own set of problems, but rising fish farming is another indicator of how severely the ocean has been depleted.

People have begun preparing for a world without wild fish. That’s the bad news. The good news is that many experts think restoring abundance to the ocean is actually totally possible—it’s just going to take some investment.

How much investment? We need to spend much, much more than tens of millions of dollars. But Bloomberg’s $53 million will still have a measurable impact, which could convince the rest of the world to pony up the extra billions that fixing the fisheries will cost.

The Case for Investing in Fisheries

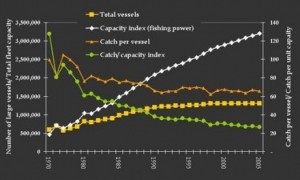

In 2008, the World Bank estimated that the global catch industry misses out on a potential $50 billion annually, and that these inefficiencies added up to a two trillion-dollar loss between 1974 and 2004. That’s the difference between what we’re currently getting out of fisheries and what we could be getting. The World Bank said that to prevent future losses and maximize profitability, two things needed to happen. First, stop trying so hard to catch fish (more on this later, but basically: stop subsidizing the global fishing fleet and investing in destructive-yet-powerful fishing gear.). Second, encourage growth in fish populations by managing them “sustainably.” This is a somewhat nebulous proposition, but it differs from the “reduce effort” dictum by focusing on local fishing communities and generating broader public interest in the health of fish stocks.

Two studies came out in 2012 further quantifying the benefits of rebuilding fish stocks. The first, published in Science, concluded that fisheries reform, broadly speaking, could generate a 56% increase in abundance and between an 8 and 40% increase in global catches. The second, published in PLOS One, estimated that rebuilding stocks would cost about $203 billion – including funding to push some fishermen out of the industry by buying back their boats – but that within twelve years the economic benefits would outweigh the costs. In line with the World Bank estimate that there’s a potential annual $50 billion to be had from global marine fishing, the authors of this study think that eventually the industry’s annual value could be $54 billion rather than the current negative-$12 billion.

What Can $53 Million Do?

The Bloomberg project to “save the oceans and feed the world” is called the Vibrant Oceans Initiative. Over the next five years, Bloomberg Philanthropies is going to dole out $53 million to three organizations to fund specific fisheries reforms in Brazil, Chile, and the Philippines. The three organizations—Oceana, Rare, and EKO Asset Management—are all based in the U.S.

…Oceana is a giant advocacy group that campaigns for international policy changes for the ocean. Rare’s signature strategy is training conservation leaders in local communities around the world; its contribution to the Vibrant Oceans Initiative will be about on-the-ground engagement with fishermen in Brazil and the Philippines. (Bruce Barcott wrote an excellent report on this approach, which depends on developing a community that sets limits for itself, a few years ago.)Of particular interest is EKO’s role in the partnership. The investment firm will design opportunities for investors to fund schemes that reward fishermen (and industrial fleets) for implementing changes, and earn shares of the returns that hopefully come about from those changes.

EKO works in the burgeoning field of “impact investing“—also known as socially responsible investing or “philanthrocapitalism.” This type of investing has been put to work against social problems—think Kiva, the Acumen Fund, Ashoka—but hasn’t been applied to conservation issues with the same fervor. “I think it’s still a relatively young, immature market,” EKO co-founder Jason Scott said in an interview.

“The most interesting thing to us is how you develop funds and find transactions that cross a range of risk and return and impact spectrums,” said Scott. Some investors care most about high impact, and are willing to take higher risks and generate lower returns in exchange. Others “want exactly the same [return] that they’d get out of a commercial or public equity or private equity deal, and then there’s a ton of space in between.”

(click the link to read the rest of the article…http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/02/bloombergs-new-plan-save-the-ocean-feed-the-world/283546/)

Leave a comment