Extreme Weather in this El Niño Year

What a difference a few months makes! When we sailed in Sardinia in July, the weather conditions were calm with light to moderate breezes and sunny skies. Then, just two months later, a rare Cyclone ripped apart this beautiful area of Italy, causing death and destruction. Our heartfelt prayers are with all the Sardos who have been affected by this tragic extreme weather.

Sardinia September 2015:

The same region of Sardinia when we were there in June/ July 2015:

Sardinia’s deadly weather occurred in a year already notable for many unusual and extreme weather phenomena.

Sardinia’s deadly weather occurred in a year already notable for many unusual and extreme weather phenomena.

What is responsible for the severe weather? According to scientists, it’s El Niño, a weather pattern of above-normal temperatures in the Pacific Ocean that comes along every 2-7 years. That sounds pretty benign, but El Niño starts a reaction that can cause devastating conditions around the world. And not only is 2015-2016 an El Niño year, it promises to be a longer and more severe El Niño than usual. This means worse heat, worse blizzards, worse flooding, and worse tornadoes, hurricanes and cyclones (a storm reaching at least 74 mph)

What does El Niño mean for sailors specifically? Most likely, weather will be more extreme than our Pilot Charts predict, with storms being stronger than normal and weather conditions being more extreme through the spring of 2016. Our marine insurance company, Pantaenius, sent us this information, which we’re sharing to help our readers. We wish you all fair winds, but if you’re affected by El Niño or severe weather, stay safe!

Because of El Niño, sailors can expect:

- Lighter trade winds than normal—and sometimes no wind at all—in the Northern Pacific.

- Weather forecasts throughout the Pacific that are uncertain and can change quickly.

- Greater number of tropical cyclones and increased chance of hurricanes in the Eastern and Central Pacific.

- Stronger and more frequent storms in Southern California

- More frequent occurrence of thunderstorms and high winds (up to 50 – 60 knots) in the ITCZ, also known as the doldrums.

An about-face in trade winds.

During El Niño, Pacific Ocean equatorial trade winds not only become lighter and weaker, but also sometimes shift their direction. Under normal conditions, trade winds over the equatorial Pacific blow from east to west. As a result of this wind forcing, warmer water is pushed westward along the Equator and piles up near Indonesia. Under El Niño conditions, trade wind speeds become lighter than normal. Since westward wind forcing is less, the warmer water piled up in the Western equatorial Pacific sloshes back towards the lower water levels in the east. Enhanced convection and precipitation follow these warmer waters eastward under the warmer water to the Central Pacific. Accompanying the enhanced convection is the shift in persistent thunderstorms from the Western to the Central Pacific. In addition, the anomalous higher sea surface temperatures in the deep tropics sometimes trigger the weaker trade winds to reverse direction, producing eastward wind bursts.

An increase in tropical cyclones.

During El Niño, expect a higher number of tropical cyclones in the Eastern Pacific—generally two to three times the normal amount, depending on the sea surface temperature anomalies. Tropical cyclones typically need sea surface temperatures of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit to form—as well as sufficient heat content at depth, among other parameters.

Changes in surface air pressure. During El Niño, there’s a seesaw shift in surface air pressure between French Polynesia and Darwin, Australia. French Polynesia has lower than normal air pressure, while Darwin has higher. These anomalous changes in air pressure, coupled with differences in sea surface temperature, are thought to reduce vertical wind shear and alter jet stream patterns in the Northern Pacific, as well as produce other global weather phenomenon.

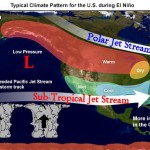

A variation in jet stream patterns.

Another weather feature common with El Niño is a shift in the jet stream patterns, making some areas—like Southern California—more susceptible to strong and more frequent storms.

Decreased wind shear and greater risk of hurricanes.

During El Niño, the tropical Atlantic Ocean has less activity due to increased vertical wind shear across the region. On the flip side, however, the tropical Pacific Ocean east of the dateline has above-normal activity, due to water temperatures above average and decreased wind shear. Most of the recorded Eastern Pacific category five hurricanes have occurred during El Niño years.

Strong storms and high winds in the ITCZ.

The Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is a relatively narrow band in the tropics where the trade winds of the north and south Eastern Pacific Oceans come together. The converging air has no place to go but up—or vertically—in the atmosphere. This induced convection is part of the reason the area is known for severe thunderstorms. Even deeper, widespread convection occurs during El Niño, leading to stronger and more abundant thunderstorms with heavy rain showers and down draft winds at the surface that can reach 50 to 60 knots!

Staying Out of Harm’s Way

To protect your vessel, as well as its precious cargo (crew, family, friends) while voyaging in the Pacific during El Niño, follow these safety tips:

Go the extra mile when planning your route.

Even the shortest voyage requires checking the forecast for potential volatile weather along your route. But keep in mind that weather forecast models during El Niño are more variable and more challenging for experts to predict. So, always double-check the forecast before casting off. While underway, tune into your VHF radio to the NOAA broadcast and surf coastal weather websites to get a full weather update at least every 12 hours—or more frequent as conditions warrant.

Have a Plan B.

Changing and more variable weather during El Niño calls for alternate route plans when conditions become unexpectedly adverse. So, be prepared to pull into port and wait things out. Another option: check maps and weather data to see if heading further out to sea may mean more manageable winds.

Pack plenty of extra provisions. If you’re sailing, remember that North Pacific trade winds are often lighter and weaker—even nonexistent—during El Niño. This means that a planned 13-day trip could take much more time. For example, a general rule of thumb is to add two to four days on a voyage from U.S. mainland to Hawaii, and four to six days returning from Hawaii. Extra fuel is recommended for motorsailing during extended periods of light winds. Also, be sure to pack extra food, water and suntan lotion!

Use a weather routing service.

Pantaenius recommends partnering with a professional weather routing service every time you cruise, but it’s a particularly smart move during El Niño. Most credentialed, qualified marine meteorologists can track both your vessel and the weather along your route. They can provide immediate alerts of adverse weather lying in your path. Experienced marine meteorologists can also offer recommendations to avoid dangerous weather that might significantly reduce catastrophic damage to your vessel or injury to crew and passengers.

Weather information provided by Rick Shema, a Certified Consulting Meteorologist based in Kailua, Hawaii. You can contact Rick by phone at 1-800-254-2525 or by visiting www.weatherguy.com.

< = Most recently, Hurricane Patricia’s wrath in the Pacific:

Leave a comment