Two Families Shipwreck on Coral Reefs in the South Pacific

When a sailing voyage comes to a sudden, violent end, no matter the cause or circumstances, it’s a terrible tragedy. Two vivacious cruising families who were sailing across the Pacific Ocean met this fate recently. Americans Danny and Belinda Gavotos and their four teenaged children, on Tanda Malaika, ran aground south of Huahine and a very experienced British sailor, Bobby Cooper and his wife, Cheryl, and their two children ran aground on Beveridge Reef near Niue. Our hearts go out to both families for what they endured, and the losses of their homes. We are sharing this post in hopes that the kindness of strangers will help them rebuild their lives, and so more of us sailors will learn lessons so this never happens again.

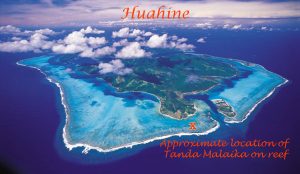

a map showing where Tanda Malaika sits on the reef

Huahine Reef Grounding

Tanda Malaika left Moorea early one morning in July and tried to make Huahine by nightfall, but sadly they didn’t make it. After dark at about 8 o’clock in the evening, they ran aground on the unforgiving coral reef that stretches around the southern end of the island. I put an “X” on this aerial view of the southern part of Huahini Iti to show where Tanda Malaika crashed.

It’s hard to imagine how awful the feeling must have been to hit the reef, their peace shattered by the screaming sound of ripping fiberglass and metal and the sickening thud of everything around them tumbling and falling as all forward momentum came to a sudden, lurching stop against razor sharp coral. Thankfully, the family was rescued and no one was badly injured.

Tanda Malaika still on the reef as we sailed by a month after her grounding

As horrible as Tanda Malaika’s accident was, hats off to Leopard catamarans for building a sturdy hull that would keep this family safe until they could be rescued. The hulls were cut up and fractured but did not fall apart on the reef. Despite the continual battering by waves, the boat still sits on the reef a month after the accident.

Because Tanda Malaika did not break up or slide off the reef, the family was able to remove everything of value that was not attached to the hull – engines, generator, dive compressor, lithium batteries, etc. Many of those items are for sale on Huahine. You can ask at the Huahine Yacht Club in Fare (tel:+689 40 68 70 81) about how to be put in touch with the agent selling the goods.

You can read more about the Gavotos family and their recounting of what happened – https://adventuresofatribe.com/2017/07/23/mayday/ . They are seeking support to rebuild their lives through a gofundme campaign https://www.gofundme.com/helprescuethetribe

Beveridge Reef Grounding

On August 30th, another family was shipwrecked after running aground on a reef, this one the Beveridge Reef about 15o miles southeast of Niue. Beveridge is an atoll we plan to stop at to dive because the visibility is supposed to be unparalleled. The lagoon inside the reef is decent shelter if we need to wait out weather on our long passage to Tonga. By a stroke of great luck, there was another boat inside the lagoon when the Coopers struck the reef and the crew on that boat came to their immediate assistance. They were even able to pull the stricken boat off the reef into the lagoon. It’s unclear the condition of the boat and whether it is salvageable. To support the Bobby, Cheryl, Lauren and Robbie Cooper https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/patrickanna-whetter-1

These tragic accidents bring to mind yet another shipwreck on a coral reef of a French Polynesian island that happened to a family from San Diego a few years ago. They hit the reef at Manuae (also known as the Scilly Atoll), which we will sail past on our way from Maupiti toward Tonga. In their harrowing experience, the father/husband was grievously injured when the mast came down on his leg. The story is mesmerizing and was turned into an excellent book called “Black Wave.”

It’s something of a miracle that the Gavotos and Cooper families emerged from their reef groundings without serious injuries. Black Wave reminds us how relatively lucky these families were in the outcomes of their tragedies and also how incredibly dangerous it can be to run aground on coral. What can we learn from these shipwrecks to make sure this never happens to us?

Lessons One: Approach Coral Reefs in Good Light if Possible

In the South Pacific, where there are so many coral reefs, it’s imperative to time arrival at new islands in daylight. Approaching coral reefs or areas with coral “bommies” – smaller, free-standing coral heads – without good visibility (and that’s the sun overhead, bright and behind your line of vision) is always a risk. We left many atolls in the Tuamotos in the evening to arrive at the next one in the early morning. We even had to slow down or “tread water” outside a pass to wait for good light because it’s not possible to see coral except wearing your best polarized sunglasses with sunshine overhead and behind you to shine light on the water in front of you.

Lessons Two: Rely on the Right Charts in the South Pacific

For the inevitable multi-day crossings, bluewater cruisers have no choice but to sail at night. In those cases, we turn our radar on every 20 minutes because it will pick up submerged reefs and show us a danger even on a moonless night.

It’s also important to choose charting resources carefully. Both these families, and the family featured in the Black Wave book I discuss below, said they did not see the reefs they hit on their chartplotters.

This highlights a super-critical lesson. Charting in the South Pacific is not the same as relying on charts in other parts of the world.

Some charts, especially paper charts that are based on readings from Captain Cook’s day, are notoriously inaccurate in the South Pacific. The best charting resources are based on satellite imagery, but even all of them are not infallible.

As for the Beveridge Reef, we can see it on Navionics and iNavx charts, and on our Furuno chartplotter – BUT ONLY WHEN THE FURUNO CHART IS ZOOMED IN TO ABOUT 35 Nautical Miles across. If the chartplotter is more zoomed out than that, Beveridge Reef is not visible!

We will save a full-length discussion of navigating in the South Pacific for another post, but the best advice we got before venturing into this coral strewn cruising area was to supplement our standard navigation apps and built-in system with satellite imagery and to download satellite images of all the areas where we’d be sailing before the trip. This takes advance preparation, but the visibility it gives is well worth the trouble. We use Google Earth, OpenCPN, and Tallon to view these satellite images in addition to our our Navionics, Furuno, MaxSea AND iNavx charting programs. It’s important to zoom in to a close-up view and look out along the path to look for reefs, “FADs” – fish attracting devices, or other hazards.

Leave a comment